As both the most populous city in Canada and the city with the twelfth-highest average property cost in the world, Toronto has the largest population of homeless, underhoused, and precariously-housed people in the country.

Toronto-based charitable organization Fred Victor reports that over 10,000 people in Toronto sleep in shelters, respite centres, or outdoors every night. Approximately 333,060 people are on the waiting list for city-subsidized housing.

The coronavirus has had a disproportionately difficult effect on Toronto's economically marginalized.

Ontario's Landlord and Tenant Board continues to hold online "blitz" hearings and issue eviction orders. Shelters, at or over maximum capacity nightly, fail to abide by physical distancing bylaws. The homeless are five times more likely to die of COVID-19.

Despite the median rental price for a one-bedroom apartment in Toronto being 20% lower than it was at the same time last year, the supply of affordable housing in Toronto continues to decline.

The ironically-named Tenant Protection Act of 1997 introduced vacancy decontrol to Ontario, which enables landlords to charge whatever they wish for rent once a unit becomes vacant.

Vacancy decontrol incentivizes predatory eviction: harassment, haphazard maintenance, and 'renovictions' are tactics commonly used to replace existing tenants with those willing and able to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars more for the same living space.

Meanwhile, rooming houses and hotels serving Toronto's economically marginalized continue to be demolished and replaced by condos.

Long-term solutions for housing are necessary. Social housing providers like Toronto Community Housing, Fred Victor and Homes First help the homeless, underhoused, and precariously-housed achieve safe and stable living conditions.

During the pandemic, it costs taxpayers an average of $6000 a month to operate a single shelter bed. Conversely, a single supportive housing unit costs an average of $2000.

Homes First operates five shelters and fourteen housing sites throughout Toronto. They house and support more than 1,200 people, with a focus on assisting the chronically homeless, people with mental health and addictions issues, and seniors.

The organization claims that the average cost to the public of one of its housing units is $1,545 a month.

33-year-old Erika and her two teenage daughters have lived in a Homes First property for almost five years. She has requested not to specify the address, out of concern that her ex-partner may attempt to find them.

33-year-old Erika and her two teenage daughters have lived in a Homes First property for almost five years. She has requested not to specify the address, out of concern that her ex-partner may attempt to find them.

Born in the Czech Republic and of mixed Czechoslovakian-Romani ancestry, Erika first came to Toronto in 2014. She lived with her ex-partner in his family's house until their separation in 2016. An ocean apart from her support networks, Erika and her daughters had no place to go.

"I don't have any family here. We were on the street and it was raining. We were able to go to a women's shelter, and while there they helped me look for housing. We stayed in a shelter outside of the city, because everything in the city was full," she told blogTO.

"One day, my worker from the shelter told me that they found a place to stay. They gave me the information, told me when I had to be there and how to make a deposit, and that was that."

Erika works from home as an artist and designer, using the name Arcadia Gsine. Her work is influenced by African-Canadian culture, including her friends, colleagues, and the music of her partner, Gene King.

She won the Homes First Wanda's Arts Awards in 2018, 2019, and 2020. She donated the award bursary from her first victory to the shelter that helped her and her daughters in their time of need.

She won the Homes First Wanda's Arts Awards in 2018, 2019, and 2020. She donated the award bursary from her first victory to the shelter that helped her and her daughters in their time of need.

"My inspiration for my art comes from emotion. If I'm not mad or sad or happy, I can't paint. Mostly, it's from anger. It calms me down to paint. It's my expression. It has made me less shy."

Since moving to the neighbourhood, Erika and her daughters have flourished, even during the challenges presented by COVID-19. "I'm not driving, so having everything like groceries nearby is important," she said.

Erika's two daughters, ages 14 and 15, attend schools nearby. Both have been e-learning during school closures mandated by Ontario's lockdown measures.

"It is harder, because sometimes the connection is not good. It's happened twice that a teacher hasn't shown up. They are both using their own laptops now, but before, the school sent laptops for children that didn't have them. Except, they didn't work."

Prior to Toronto's first lockdown in March 2020, Erika organized and participated in live events and art shows throughout the city. During the lockdown, she began live-streaming herself painting on Facebook.

"The pandemic has changed our lives a lot. I'm not a social person, but I like to socialize. Right now, when we can't see as many people, just our own bubbles, there is a challenge with connection."

"You can keep touch and check on people by Messenger, but it's stressing. It's stressing to see more people getting into a depression. At first, everything started online. Parties, events. But now, not many people are as interested, because it's not the same."

With stay-at-home orders in effect, Erika misses exploring Toronto. "I used to take long walks and just see the art on the street. Sprays, graffiti, murals. Mostly downtown or Lakeshore, but I really like The Beaches."

While speaking, Erika takes several pauses to use an inhaler, treatment for an affliction she developed in late November 2020. "I had pneumonia pretty badly. I couldn't see my doctor because of COVID priority. He basically rejected me. I was left to try to cure myself. I ended up in the walk-in clinic and they gave me this inhaler."

While speaking, Erika takes several pauses to use an inhaler, treatment for an affliction she developed in late November 2020. "I had pneumonia pretty badly. I couldn't see my doctor because of COVID priority. He basically rejected me. I was left to try to cure myself. I ended up in the walk-in clinic and they gave me this inhaler."

Through Homes First, Erika receives assistance from workers of varying skills and specializations. One performs physical maintenance on her home.

Another works closely with her children, helping to facilitate their development and education. Another is helping her apply for permanent residency in Canada, though the process has been slowed by the coronavirus.

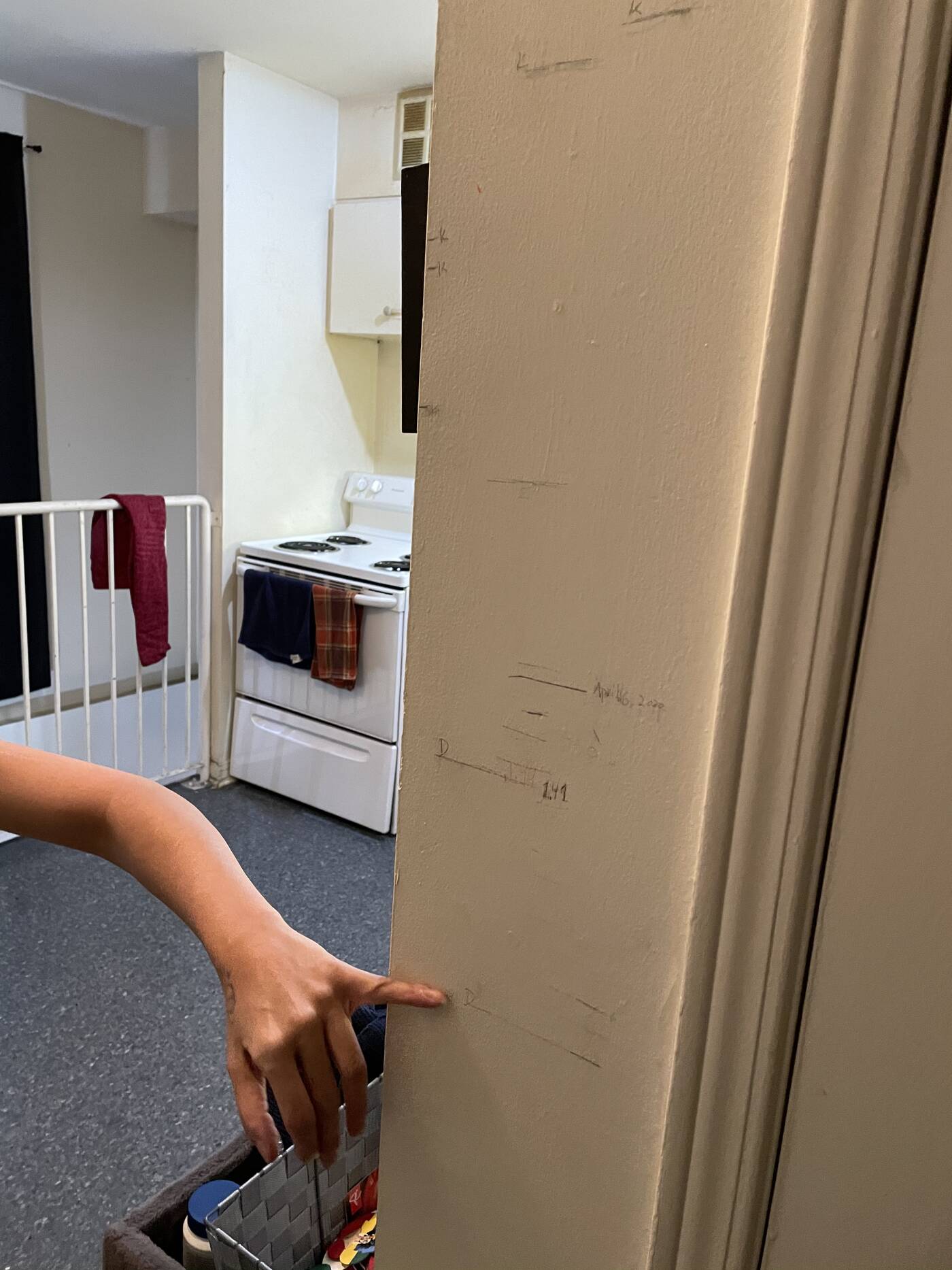

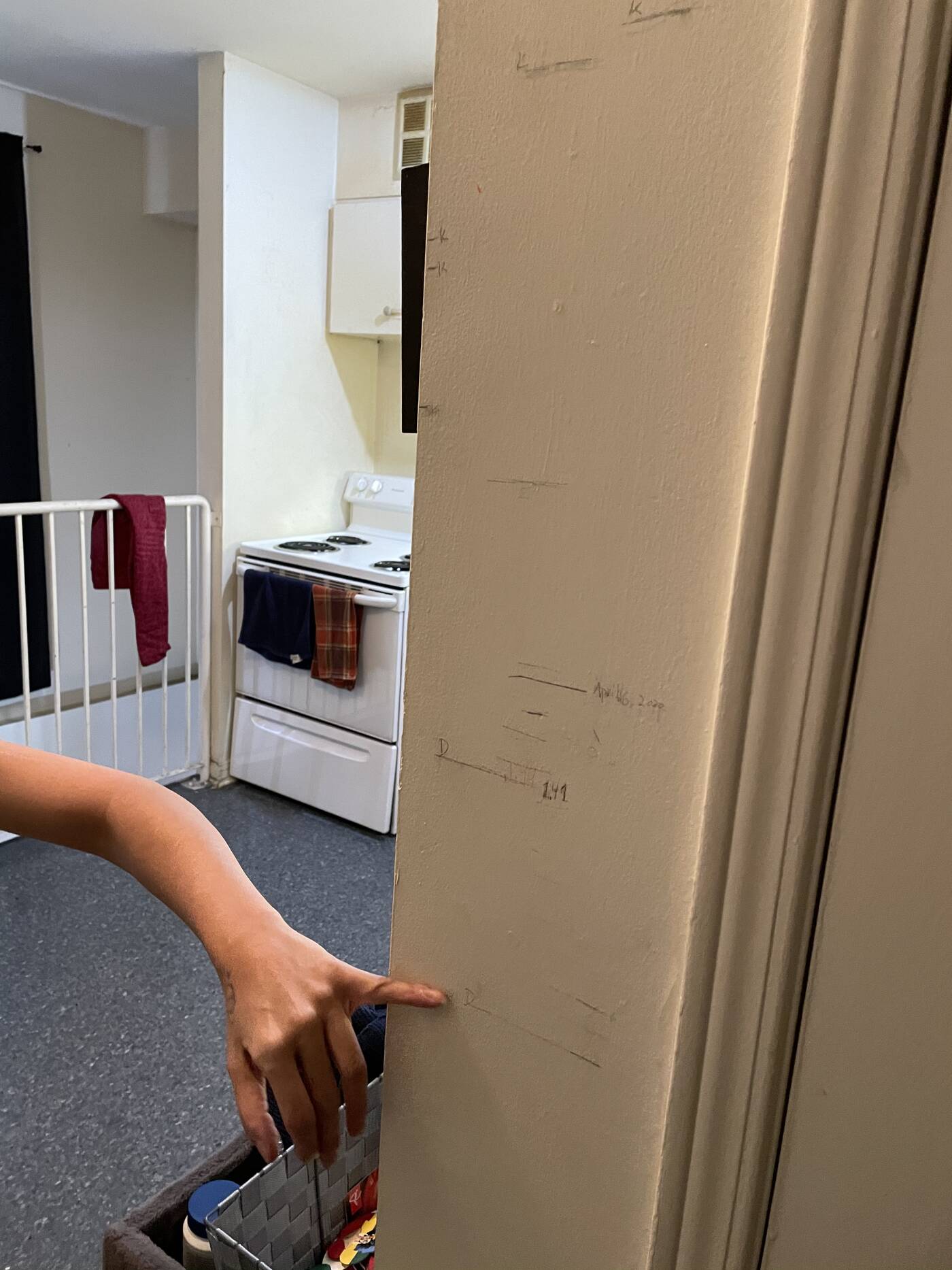

It is because of publicly-funded charitable organizations that thousands of people in Toronto, including Erika and her daughters, have been able to build lives for themselves. Erika's eyes smile as she points to pencil-markings on a wall, chronicling the growth of her children.

"I'm not on the street. Because of their help, we can live. I love living in this city. I love the people of Toronto, even if sometimes they can be rude. It's about the experience, the inspiration, and making memories."

33-year-old Erika and her two teenage daughters have lived in a Homes First property for almost five years. She has requested not to specify the address, out of concern that her ex-partner may attempt to find them.

33-year-old Erika and her two teenage daughters have lived in a Homes First property for almost five years. She has requested not to specify the address, out of concern that her ex-partner may attempt to find them. She won the Homes First

She won the Homes First  While speaking, Erika takes several pauses to use an inhaler, treatment for an affliction she developed in late November 2020. "I had pneumonia pretty badly. I couldn't see my doctor because of COVID priority. He basically rejected me. I was left to try to cure myself. I ended up in the walk-in clinic and they gave me this inhaler."

While speaking, Erika takes several pauses to use an inhaler, treatment for an affliction she developed in late November 2020. "I had pneumonia pretty badly. I couldn't see my doctor because of COVID priority. He basically rejected me. I was left to try to cure myself. I ended up in the walk-in clinic and they gave me this inhaler."