Standing on Toronto's shore, you could be forgiven for thinking that the view to the Island is as old as the city's longest operating ferry. The PS Trillium entered service in 1910, but when it first trekked across the inner harbour, the trip was significantly longer than it is today.

Toronto's waterfront has changed continually since the area we call home was settled, but it was transformed entirely in the 1920s when various in-fill efforts expanded the city a few hundred metres southward.

It's difficult to call to mind just how much the waterfront has changed over the last century, but if the curiosity ever strikes you, take a trip to the Harbour Commission Building and saunter back towards Lake Shore Boulevard.

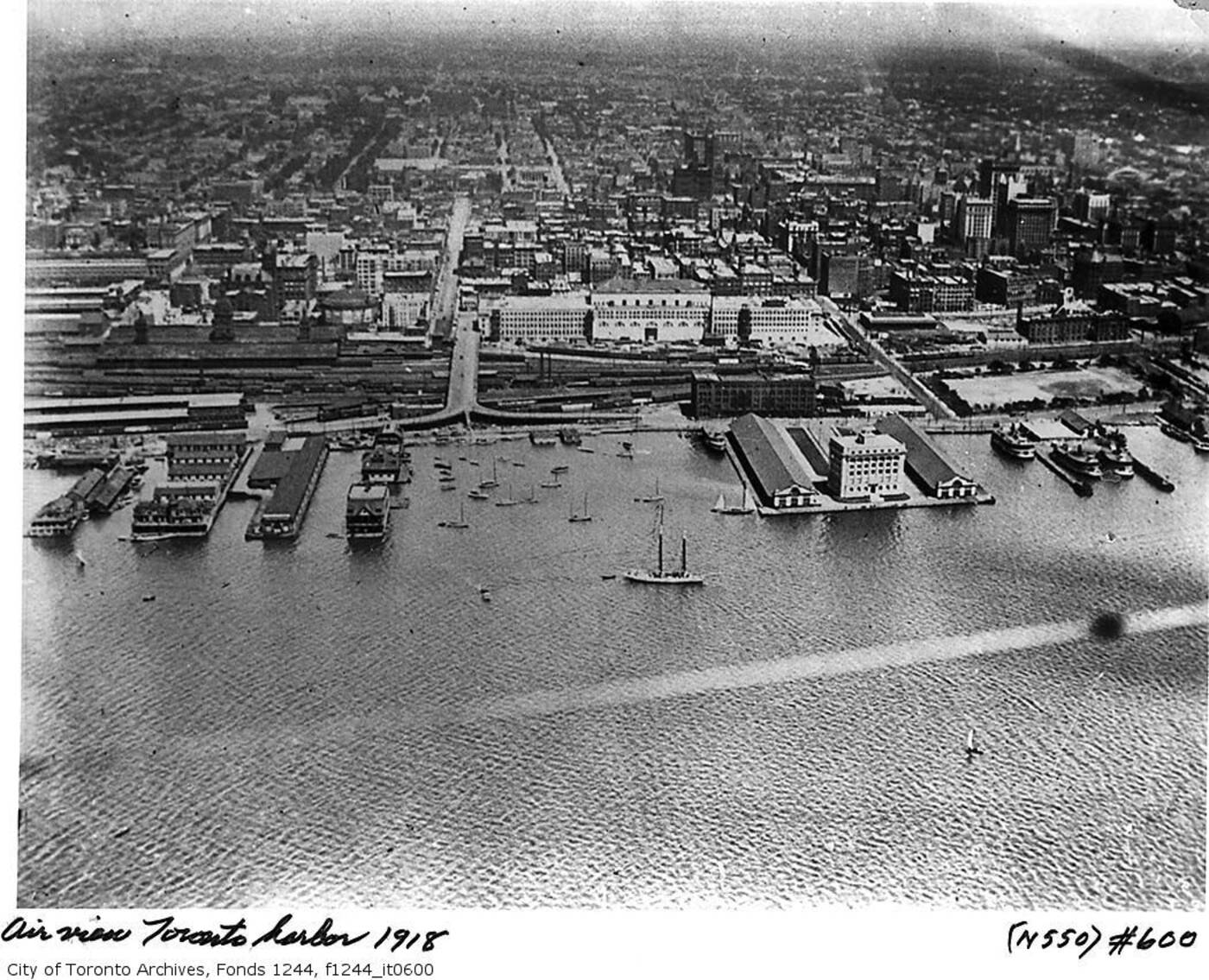

Now surrounded by in-filled land, the Harbour Commission Building once jutted out into the lake.

Where the rear parking lot meets the street is about the point that the shoreline began at the turn of the century. Go back 50 more years, and it was somewhere around where Union Station is presently located.

Among the things claimed by the southward expanding city is Frederick Augustus Knapp's "roller boat," a 110 feet long, 22 feet tall cylindrical vessel that was meant to revolutionize sea travel, but was beset by all manner of problems and eventually consumed by harbour mud.

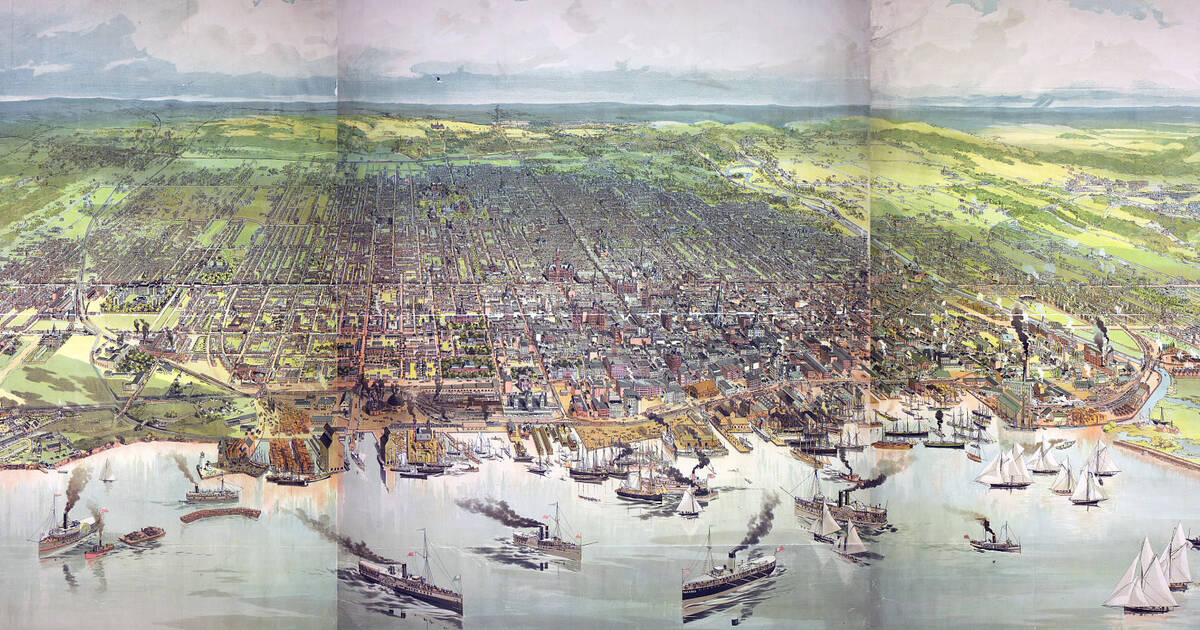

Toronto's waterfront in 1854. Painting by John Howard via the Toronto Archives.

It's hard to imagine these days, but before these efforts to fill in the lake, Toronto was once a small waterfront community. When the city was incorporated in 1834, much of the developed area was within a few minutes walk of the lake.

The Plan of York in 1818. Note the curve in the shoreline between the two visible piers. This is can still be seen in the route of the Esplanade.

Take a look at the city's earliest street grid, as laid out by Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, for a sense of just how much the city's earliest form was determined by its relationship with the waterfront.

The southward bend the Esplanade does just west of Jarvis St., which still exists today, follows the route of the old shoreline. Even 50 years later, the shore had been extended slightly south via various wharves, but the angle of the street remains preserved.

Looking east along the Esplanade in 1894. Photo via the Toronto Archives.

By the late 19th century, Toronto's port was a bustling place. The city had already been extended southward to accommodate the expanding railway lands south of Front St. and numerous piers were built for the shipping traffic in the harbour.

1911 was a crucial year for the city's waterfront, as it marked the creation of the Toronto Harbour Commission, an agency tasked with managing the now very busy shoreline. A year after its formation, a plan was revealed to alter the waterfront in a dramatic way.

Once at the tip of the city, the Harbour Commission Building is surrounded by new land in 1929. The previous shoreline is visible to the far right of the photo. Photo via the Toronto Public Library.

Over the next couple of decades, massive efforts were undertaken to extend the shoreline into the lake and to dredge the harbour to a level of at least seven metres to allow for the passage of the heavy freighters that were now cruising the Great Lakes.

The footprint of the central waterfront we know today has its roots in the expansion that took place in the 1920s. Subsequent alterations through the mid -century period involved filling in the spaces between piers as industrial activity calmed in the port.

Queens Quay Terminal and the Harbourfront in the late 1970s before their respective makeovers. Photo via Harbourfront Centre.

Toronto's lakefront was a particularly gritty place in the late 1970s. Shipping traffic had calmed in the harbour, but industrial infrastructure remained pretty much everywhere. From the Maple Leaf and Victory Soya Mills to Queens Quay Terminal to Pier 6, the waterfront was a far cry from the recreation-heavy corridor we have today.

Toronto could have almost passed for a Rust Belt city during this period, but change was already afoot. The Westin Harbour Castle was built in 1975 and would usher in period of intense transformation over the following two decades, including the birth of Harbourfront Centre and the rise of lakefront condos.

The Toronto waterfront in recent years. Photo by Empty Quarter.

While the city's waterfront has continued to evolve, the most significant changes in the last 20 years have taken place on the reclaimed land to the north of the current shoreline.

It's amazing to think that the entire area we now call South Core is built on land that derives from in-fill efforts that took place a century ago.

Where once the lake was a leisurely stroll from King St., now it's a hike through towers, stadiums, and highways built on land of our own making.

0 comments:

Post a Comment