Small gated roads with lead into a mid-sized Toronto park near Mount Pleasant Road and St. Clair Avenue East in Rosedale.

Hundreds walk along these unnamed roads from Douglas Drive and Roxborough Drive every day, many unaware of the rich history of political royalty that followed these paths generations before.

The name Chorley Park has lived two very different existences. Now little more than a public park and a popular stop on Toronto's trail system, Chorley Park was once the site of a lavish mansion whose opulence would go unchallenged even today.

Chorley Park stood as the third and last in Ontario's short line of Government Houses, built between 1868 and 1870 and demolished just over 90 years later.

Chorley Park, 1930. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 10086

A designated home for the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, this official vice-regal residence was a cut above the official homes of many heads of state.

Synonymous with government spending and the era's excesses, the mansion was closed under political pressure during the Great Depression and ordered demolished back in 1960. Chorley Park was unceremoniously torn down the following year, all in the name of austerity.

The history and eventual loss of the Government House have been well-documented, an act of architectural desecration that would be unthinkable with today's understanding of heritage.

Images of the demolished mansion still manage to conjure up feelings of outrage decades after the fact.

Less attention has been paid to the fractured architectural legacy that remains on the site to this day.

Chorley Park in 2021. Photo by Jack Landau.

Chorley Park was added to the City's park system shortly after the house was demolished, and clues of its past existence are present throughout the public space.

Chorley Park as it looks in 2021. Photo by Jack Landau.

Roads lead into the park from Douglas Drive and Roxborough Drive, converging at a landscaped traffic circle.

From the Douglas Drive entrance, a Bike Share station and standard Toronto Parks signage provide little clues as to the road's former use.

Douglas Drive entrance to Chorley Park. Photo by Jack Landau.

The road leading into the park from Roxborough provides a bit more in the way of hints, including one of the original gateposts.

Roxborough Drive entrance to Chorley Park. Photo by Jack Landau.

Road edges paved in brick add another touch of history to the walk into the park.

Brick-paved road edges in Chorley Park. Photo by Jack Landau.

The most noticeable remnant of the former Government House is a bridge connecting the raised retaining walls of the traffic circle and the mansion's former forecourt, where the early automobiles of Ontario's movers and shakers once parked.

Roundabout at Chorley Park. Photo by Jack Landau.

The underside of the bridge can be accessed via a small set of stone stairs.

Stairs leading to underside of bridge. Photo by Jack Landau.

From here, you can get up close and personal with a bridge that now offers more in the way of form than function.

Chorley Park's bridge. Photo by Jack Landau

Other clues are visible for those willing to take the time exploring, like depressions in the park's grass that offer up a rough outline of where the Government House foundations once stood.

Depressions in the land at the north edge of the park. Photo by Jack Landau.

The City's page for the five-hectare park that occupied the former grounds seems entirely unconcerned with the site's rich history, mentioning only its "mature tree canopy and picnic tables" and its views of the Don River Valley and connections to adjoining trails.

A plaque fixed to a boulder was previously the only on-site recognition of what once existed here, installed by the Toronto Historical Board in 1978 and since removed.

Site of removed plaque at Chorley Park. Photo by Jack Landau.

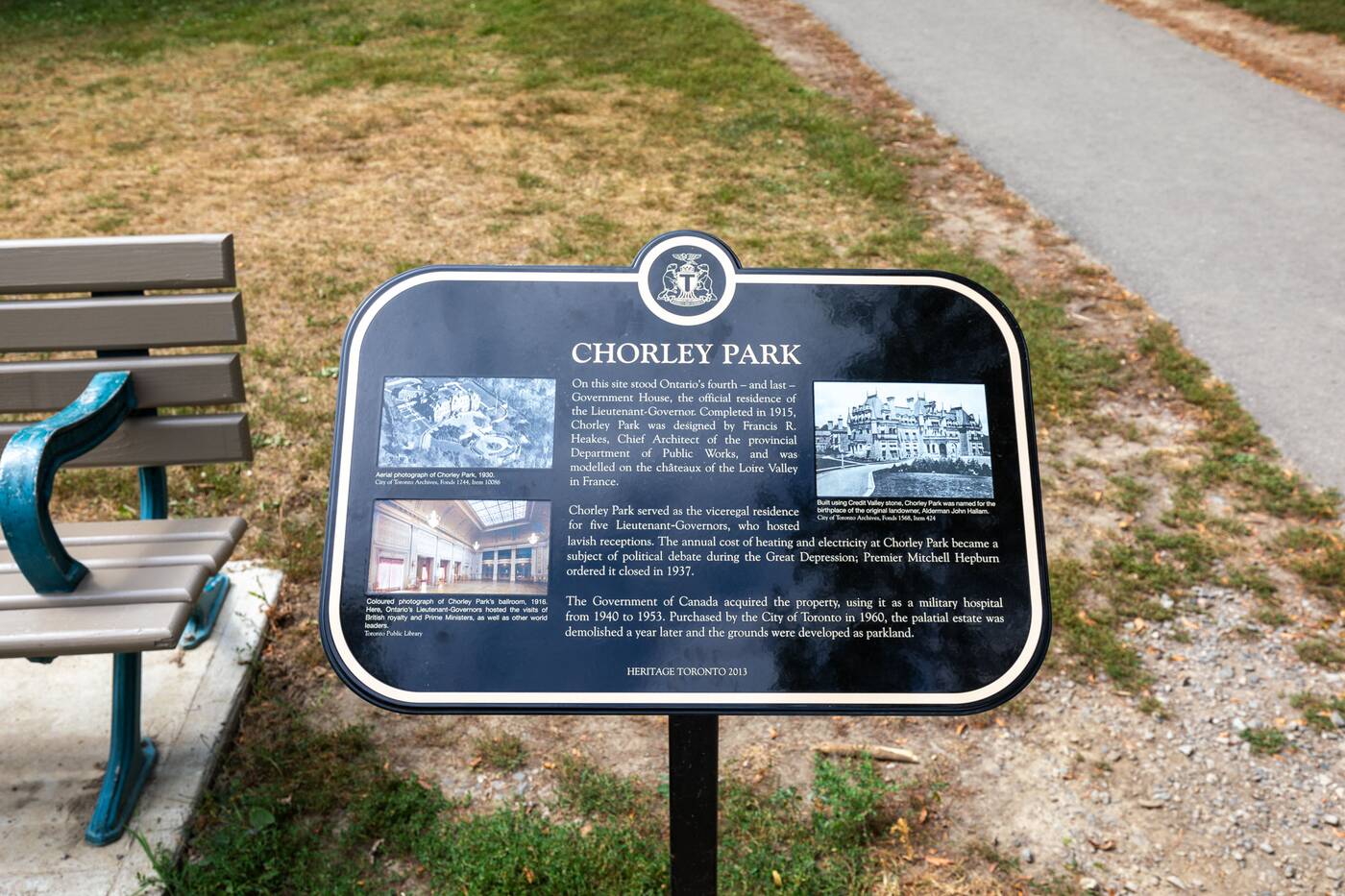

The plaque was replaced by Heritage Toronto in 2013 with a standalone sign, now offering up a few pictures of what once was.

On this site stood Ontario's fourth — and last — Government House, the official residence of the Lieutenant-Governor. Completed in 1915, Chorley Park was designed by Francis R. Heakes, Chief Architect of the Provincial Department of Public Works, and was modelled on the chateaux of the Loire Valley in France.

Chorley Park served as viceregal residence for five Lieutenant-Governors, who hosted lavish receptions. The annual cost of heating and electricity at Chorley Park became a subject of political debate during the Great Depression; Premier Mitchell Hepburn ordered it closed in 1937.

The Government of Canada acquired the property, using it as a military hospital from 1940 to 1953. Purchased by the City of Toronto in 1960, the palatial estate was demolished a year later and the grounds were developed as parkland.

Plaque at Chorley Park. Photo by Jack Landau.

This pittance of acknowledgement is not nearly the recognition the former Government House deserves, though one could say that a lack of an interpretive installation on site adds to the mystery of what could be the greatest home ever demolished in Toronto.

0 comments:

Post a Comment